Over the last few decades we have gained experience designing, building, fixing and transforming the security operations in organisations that include mid-caps, global industrials, Big 4 consultancies and Government Departments. In the process we have seen examples of the good, the bad, and the downright ugly. During this time, the concept of the Security Operations Centre (SOC) has changed, and the security industry has renamed elements of it every two or three years. But the fundamentals have remained largely the same. This whitepaper shares some of the lessons that we have accumulated (but shouldn’t be considered a recipe for success — that would require tailoring to the context, priorities, resources and objectives of the organisation in question).

Misconceptions

One of the main reasons why many organisations are consistently frustrated or disappointed by their SOC is because it is frequently misunderstood.

A common misconception is to think of the SOC as a “Security Service Desk” where the tasks can be predicted and scripted, and are executed on demand. Level 1 analysts might be expected to just follow the scripts, and only escalate when edge cases stray outside of the defined task scope. But security incidents are rarely predictable and their start point will on most occasions be ambiguous. It takes a curious, qualified and exercised mind to look at the information available and decide whether it is a false alarm or a potentially dangerous incident.

Another is to think of the SOC as a stand alone function that just sits there, and only interacts when it detects a security issue that needs attention. The problem with this interpretation is that the SOC exists to detect unusual things that are happening in the business. To do that the SOC needs to understand what is normal in the business. Context is vital, such as understanding the core business processes and how they interact. This is essential not just to be able to interpret the data and identify the genuine incidents. It is even more important if the team are going to be able to prioritise those incidents, and escalate those that are most threatening to the business.

Mission and value proposition

So what is the mission of the SOC. It’s main effort has always been to reliably detect dangerous activity quickly enough and with enough insight and intelligence that a response can to be executed before damage is done. Detection and response. Yes, there are other, subsidiary tasks that the SOC can contribute to, but they relate to the wider value proposition. The mission is to detect and enable a response that neutralises the threat to the business, or minimises the impact of the threat so that the business can recover.

From our experience though, the SOC can deliver significantly greater value beyond the “detect and respond”. Managed Security Service Providers (MSSPs) will frequently find that their customers’ CIOs benefit as much from their service as the CISOs do. This is because the SOC is able to provide exceptional IT situational awareness. What cloud services are being employed across the business? What shadow IT has been deployed? Who is using which AI service?

And the SOC, when responsive, can be a formidable control in the face of changing threats, vulnerabilities and risks. When a protective control to counter a new threat or vulnerability cannot be implemented quickly then a new use case can be deployed to cover the risk in the meantime.

People, leadership and a sense of purpose

Some tasks in life involve people operating tools; in others the tools equip the people. In the SOC we employ people for their judgement; their ability to fuse multiple sources of data, threat intelligence, business context and personal experience to diagnose a particular situation. AI may diminish this position, but we are a long way from that at the moment. The analysts play a lead role in the operation. We have found that this introduces a number of factors that affect the performance of the SOC:

Diversity. When triaging and diagnosing incidents, different perspectives and approaches help. A deeply technical analyst will look at the situation through a technical lens to identify the problem; much like a mechanic diagnosing a problem with your car. Someone with an investigatory background, perhaps from experience in law enforcement, is more likely to be led by the evidence in whatever direction it takes them. A third person, perhaps with a military background, might treat it as an intelligence puzzle, rife with ambiguity, and be steered by an understanding of the way that the bad actors operate and their likely motivation and objectives. On their own each of these types of analyst may arrive at the right conclusion, albeit taking a different journey. But with all three personas in a diverse team they can contribute and challenge each other, creating value that is greater than the sum of the parts.

…fuse multiple sources of data, threat intelligence, business context and personal experience to diagnose a particular situation

Team Cohesion. If diversity is important then this strongly implies that security operations is a team sport. The level 1 analyst being able to lean across to his neighbour, share a screen and seek a second opinion. The conversation on one side of the room that sparks a memory of a previous incident in another team member. The value of this cohesion is one of the reasons why a 100% remote working team will often struggle. But more than proximity, it demands a culture of trust. Horizontally between peers and also vertically between L1, L2 and L3 analysts. If everyone recognises that nobody has a monopoly on the right answer you are more likely to get free sharing of viewpoints and hypotheses.

Variety & Progression. Just as diversity of background can help, so rotating individuals through different roles can challenge and stretch pre-conceptions and introduce richer skills and experience. It also mitigates the risk of burn-out that is almost inevitable with cognitively demanding, high-pressure shift work. After six months in a shift rotation most people would appreciate a break analysing threat intelligence, threat hunting, or working with engineers to develop new use cases. This approach invests in a broader set of skills, and can also be useful when providing a promoted analyst with an air gap from the core team before they return at the higher seniority. Or if you are less concerned about upside opportunity than downside risk, bringing variety and new skills is going to make the costly churn that so many SOCs experience far less likely.

Leadership. Leadership should be an obvious necessity when dealing with a high performing team, composed of diverse skills and backgrounds, which needs to gel to succeed. We hesitate to mention its importance because it might be perceived as a statement of the blindingly obvious. But we have seen too many suffer where it is either absent or is more akin to administration than leadership. The end result is not just loss of performance — it also has a direct impact on retention.

Continuous content optimisation

As important as the team is, they can do nothing without effective content. This content includes the use cases — the rules and analytics that generate alerts from the logs and events — and the playbooks, whether they written down as manuals or codified in the Security Orchestration, Automation and Response (SOAR) tooling. Tuning, maintaining and developing this content needs to be correctly resourced, but too often it is excluded from the original business case and operating costs. If the threats are constantly evolving why wouldn’t the content need to be updated at a similar pace? If your digital environment (on premise and in the cloud) changes, wouldn’t you need to review your use cases and play books to ensure your coverage remains adequate?

It isn’t just about new content. It is also about the continuous process of refining existing material. Adjusting the use cases to minimise the chances of a false positive without increasing the risk that a genuine alert will go unnoticed. Removing content that is redundant because the infrastructure has been removed or other controls have been put in place. Updating content, particularly playbooks, to benefit from the lessons learnt in recent incident responses.

Managing use cases, playbooks and dependent data feeds is a core capability for a healthy SOC. If it sits in your plan as an annual review and only if you have some people who aren’t busy doing something else then the consequences may be significant when the bad actors come knocking.

Access to context

If content is King, then context is the stars and the moon. It starts at the enrichment of technical information. What services are hosted on that endpoint? What is that service account used for, what privileges does it have, where can it exercise those privileges and when was it last rotated? Some of this context might be accessible on demand but a lot of it is hard to get in a hurry.

If content is King, then context is the stars and the moon

But much of the richest context sits in the memory of the business and its people. The critical nature of a small, little used service may not be known to IT. Or the existence of a workaround that is used when an unreliable application goes down and could be a useful reversionary mode if services are under attack.

Some of this might be documented, but a lot of the questions can’t be anticipated until a particular situation arises. The only way to address those context requirements is to know who to ask, and to have the processes and relationships established that make asking the questions OK. If this doesn’t happen until an incident arises it is probably too late. The foundations need to be laid and maintained. Documented asset ownership across the business will help to signpost the relevant stakeholders. And bringing those stakeholders onto a call for a minor incident, or clarification when tuning some content, will establish the relationships and norms.

The potential scope

So far in this paper we have discussed the conceptual, organisational and people aspects of the SOC. This is for a reason. Instinctively it is natural to jump straight to the functions that you are asking it to deliver and the technologies you want to support it with. But there is value it spending time considering what you want it to achieve and how it will be best set up for success.

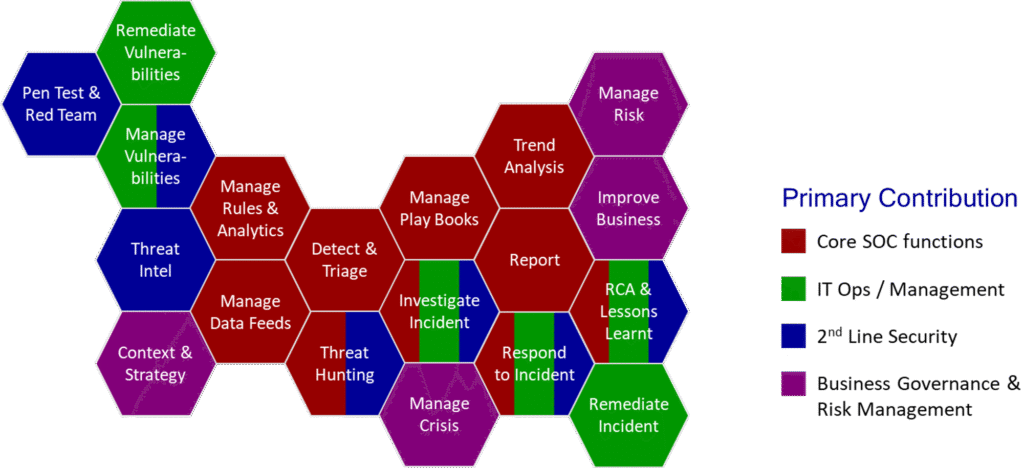

At some point though, you need to decide what you want it to do and how it should deliver those outcomes. Businesses at different levels of maturity will need different breadths and depths of functions. The figure below outlines many of the most frequent capabilities that either exist within a SOC or that adjacent to the SOC and carry a level of dependency. To an extent, it doesn’t matter where they sit in the organisation. What is important is that there are the correct interfaces and integrations between the cells.

For example, vulnerability management may well not exist within the security operations organisation. But security operations is a critical control for managing un-remediated vulnerabilities, so it is important that the function responsible for vulnerability management is able to engage with security operations and raise the requirement for new rules and analytics. This in turn may demand changes to the data feeds, and will undoubtedly require guidance to the analysts so that they can correctly triage any alerts generated. The interface is between vulnerability management and rule & analytics management, and the downstream dependencies and requirements flow from there.

As mentioned above, many organisations will not need the full spectrum. And others may have additional functions not listed here. But by deciding what functions and capabilities are required to meet the business’s risk appetite you can have confidence that the design is founded on solid business requirements.

What to out-source and what to build in-house

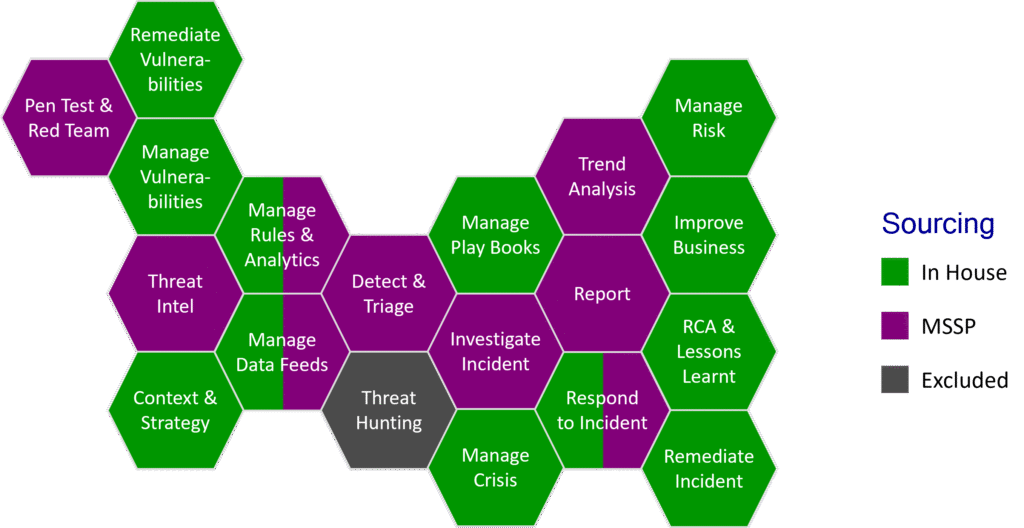

Having decided what you need it is possible to decide what to build in house and what to outsource as an external service. This is a critical decision before any implementation or transformation is executed. There are pros and cons of both options, and the strength and balance varies across the functions that are in scope.

At the core of the SOC we have the cells that contribute to detection and response. As we described earlier in the section about People, this demands a certain critical mass below which it will be difficult to deliver an effective service or value. A 24/7 service demands four shifts. In general each shift must consist of at least three people if you are going to cover holiday, sickness and accommodate other continuity and duty of care requirements. This means you will need 12 analyst (or 8 if you are very frugal and can tolerate one analyst on a shift). But you will also need tiers of experience. You can’t have the senior analyst on duty from 2200-0600 if the junior analyst who might need to consult with them is on from 0600-1400. So this will require 3-4 others to be added and available on call. You then have to ask how you will achieve any team cohesion if resources are spread so thin, or how you will deliver variety if you can’t justify a dedicated threat intelligence team to rotate people through. And who is going to develop and maintain the use cases?

This might suggest that most organisations should outsource everything, and this would be the wrong conclusion to draw. A managed security service provider should support but can’t lead in a corporate crisis. Unless you outsourced security to your IT service provider they are unlikely to be able to remediate the incident. Critically they are unlikely to have sufficient understanding of you business to be able to develop an incident response plan without your support.

Hybrid models create more granular Supplier / customer boundaries that inevitably create friction, slowing down or preventing the sharing of context. This friction is not something that you want during a crisis. It can be overcome, but the mitigations need to be design, and exercised regularly to ensure they will operate correctly.

So there are some functions that, for a particular business, might lend themselves to being outsourced in order to benefit from economies of scale and to leverage the intelligence gathered across a broader customer base. And there are others that are more likely to benefit from being retained in house so that the business can have visibility of and manage its own risk. The diagram above illustrates a common hybrid sourcing model.

Once the functions to be outsource to an MSSP have been decided some time should be spent designing the process and technical interfaces that need to be established between the in-house and the outsourced functions so that they can be built into the requirements, and contract.

Summary

Security Operations — the ability of an organisation to be able to detect security incidents, respond to them, and be in a solid position to recover from them — are probably one of the hardest and most complex elements of your security to get right. Done wrong a SOC will suck up time and money and leave you wondering where the value is. Done right it becomes the nerve centre not just of security but also of your entire digital estate.

…our advice would be to put the vendor brochures away, read this whitepaper, and give us a call if you need more support.

The key, as with any large complex programme, is to step back and spend some time building the strategy, developing the requirements, and designing a solution that is best able to deliver the right outcomes.

If you think that the first step is to choose the tools you are going to implement then our advice would be to put the vendor brochures away, read this whitepaper, and give us a call if you need more support.