Brief at the Start

Go straight to the full length version

If you don’t recognise an Asset’s value or can’t easily identify what harm it might come to then it is PROBABLY NOT AN ASSET

We introduced the idea of an Asset in Episode 1 as something of value to you or your business. We also described why it is important to start with the asset when deciding how to protect it. If you don’t recognise the value in an asset or can’t identify how that value might be harmed, then it is probably not an asset at all.

The wallet in your pocket or purse in your bag is not an asset. The money and cards in the wallet or purse are the things of value. The wallet or purse is a container. You use it partly to hold the assets together in an organised way so that they are accessible to you when you need to use them and to make it easier to prevent them being lost or stolen.

In this context, the laptop in your bag or mobile phone in your pocket is not the asset (in other contexts they may be described as assets, because sadly in life we don’t have enough words to have a different one for every different context). The personal information in your social media account, the many of the emails you have sent and received, the financial data contained in your bank account, and the video stream generated by your CCTV cameras are the things of value. They are the things that you would care about if the wrong person was able to view them, change them, or delete them.

Just as gold is valued more highly than silver, and silver more than bronze, assets have different relative values. Somethings can be easy to value, like the money in your bank account. Others are more subjective and will vary over time, such as your digital identity contained in your social media accounts. But you need to be able to classify those things that are very valuable and those that do not need to be handled with as much care.

If you can relate to an asset, and recognise its value, then you should be able to identify how it might come to harm. You do not need any deep technical expertise, or to understand how a hacker might go about their trade. You just need to be able to ask yourself how much pain would be caused if the wrong person was able to access it. Or what disasters might occur if the information was changed. Or how you would cope if it was lost forever.

Answering these questions is a good first attempt at defining the risks you are exposed to, and how intolerable those risks are.

Get the Full Version

What is an Asset

In Episode 1, I explained the importance of aligning the cyber security approach with business priorities, focusing from the outset on what we are trying to enable rather than what we are trying to prevent. This approach demands that we start with Assets. In this context, when we talk about assets, we are not talking about devices or servers. We are referring to business assets. Things that the business or organisation relies on; what they inherently value; what would cause hurt, harm or loss if compromised; or what would give someone else an unfair competitive advantage if they gained control of it.

It might be as simple as a document, as complex as an enterprise application, or as emotionally sensitive as a digital identity or persona on social media. It’s easy to get sucked into a vortex of detail in this phase. You get started, sketching a list of things in a notebook, and before you know it, you have run out of space. The aim here is not to conduct an inventory of every asset.

Classifications

We start by identifying some broad asset classifications based on their sensitivity. We should keep the number of classifications within the bounds of the Rule of 7 (see the first chapter of this series for an explanation of what Miller’s Magic Seven (+/-2) rule is). In fact, I would advise you to remain within 5 (+2/-0) for the broad classifications of sensitivity. Less than that will have insufficient granularity, and more than that will become unwieldy, making it hard to decide whether an asset sits in one classification or another.

An example might be the following:

| Classification | Description |

| Not Business (or Not Sensitive) | It requires no controls and doesn’t bother us if it is accessed, modified or removed by any unauthorised individual. In a business context, these might be personal documents generated by an employee; they may be of value to the employee but will have no relevance to the business, and terms of employment can eliminate liabilities. |

| Open | It can be shared freely but is official information or resources, so modifying or deleting it must be controlled. It may or may not be on the open internet. A public website would be Open, and the material on a Social Media account may be Open if there is no concern about who sees it. |

| Sensitive | It can be shared with discretion. It shouldn’t be placed on the open internet, and the circumstances under which a Sensitive item (or collection of similar Sensitive items) can be shared will probably be defined by a policy. Company-wide processes, policies, training material, instructions, etc, may be classified as Sensitive. They will need to be shared widely with employees and may need to be shared freely with some external partners and associates, but they could cause some harm if they fall into the wrong hands. For example, all employees should have access to and be familiar with security policies, but if a hacker had access to them, they might be able to identify a way to subvert a policy for their benefit. |

| Confidential | Confidential information could have a material impact on an organisation’s operations, health or competitiveness if compromised. Within a business context, Confidential information would probably only be shared externally under the protection of a Non-Disclosure Agreement. Internally, Confidential resources will generally be more tightly controlled and only accessible to those who need them to do their job. |

| In Strict Confidence | The most sensitive or valuable information will be held In Strict Confidence. This is equivalent to a Government’s TOP SECRET information. It could do significant harm to the organisation if compromised. For example, access to bank accounts and share-price sensitive information in a business context may be classified In Strict Confidence. If a resource of this type is shared externally it should be subject to significant extra controls, with tight limitations over who it can be shared with. For example, retained legal counsel may be authorised to receive specific resources of this type related to ongoing legal disputes, but only after due diligence has been conducted on the law firm’s own security. |

You should be able to place most of your organisation’s resources into one classification or another using a set like the one above. There may be value in sub-classifying some to provide some granularity and clarity of context. For example, Confidential resources might be given additional caveats or descriptors such as Client Confidential, Company Confidential and Personnel Confidential to cover different purposes. As we will see in future Episodes of this series, there may be minor variations in the controls applied to each of these sub-classifications. But they would all exist under the broad definition of Confidential.

Cataloguing Assets

You can now start to catalogue your assets into these Classifications. While your applications may need to be classified individually, it is best not to try to inventory individual documents except for the most important ones. Instead, it would be best if you classified the broad sensitivity of a repository, such as a shared drive or SharePoint site. This isn’t just to keep the task manageable. It also makes it easier for people to distinguish between asset sensitivity on a day-to-day basis. It is easier for someone to recognise that they need to handle a document in the HR folder to a more stringent standard than those in the Marketing share, than to assess each document on its own merits. There are tools that enable you to classify documents individually, but it is human nature to find it easier to differentiate between things on a compartmentalised basis.

You may feel that some resources don’t naturally sit within one of your classifications, particularly when it comes to a complex application, and you may need to treat these exceptions individually. But it would be best to challenge this tendency to treat everything as an exception.

An illustration of this type of asset list can be seen in the table below:

| Asset Name | Classification | Owner | Remarks |

| Intranet | Sensitive | COO | Sharepoint Site https://acmeinc.sharepoint.com/sites/Acme |

| Website | Open | Sales Director | |

| Policies | Sensitive | COO | Sharepoint Site https://acmeinc.sharepoint.com/sites/policies Modification limited to authorised group |

| Finance Teamsite | Confidential | Finance Director | Sharepoint Site https://acmeinc.sharepoint.com/sites/finance |

| Xero | Confidential | Finance Director | |

| Hubspot CRM | Confidential | Sales Director | |

| Approved Marketing Artefacts | Open | Sales Director | Sharepoint Site https://acmeinc.sharepoint.com/sites/public_marketing |

| Secret Recipe for Product X | In Strict Confidence | CEO | |

| Client Confidential Teamsite | Client Confidential | COO | Sharepoint Site https://acmeinc.sharepoint.com/sites/engagements |

| Government Client Teamsite | Client Confidential (Govt) | COO | Sharepoint Site https://acmeinc.sharepoint.com/sites/hmg_engs |

This example is simplified; you would expect it to attract additional information over time. But as it stands, this provides the information required to get started.

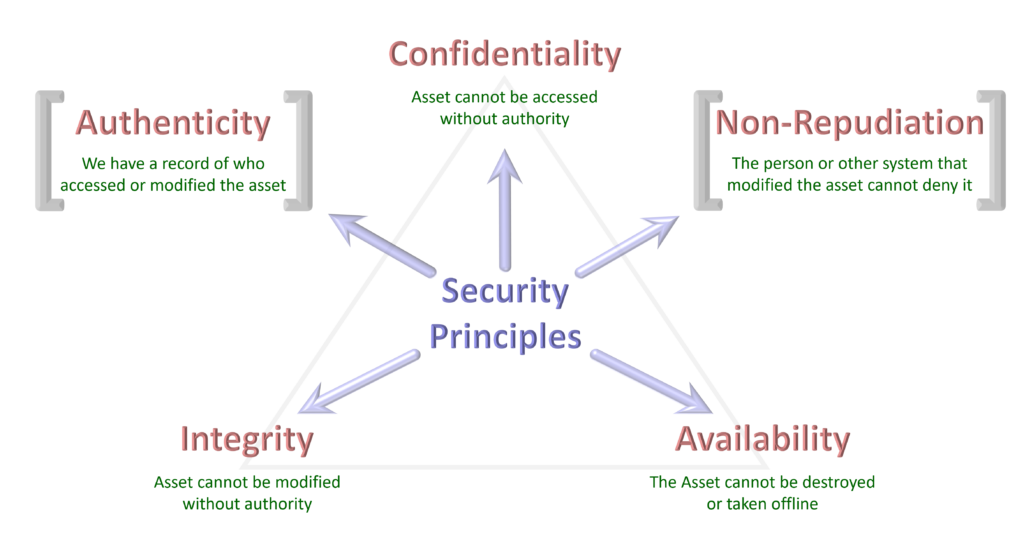

The Principles of Security

Having identified assets and their relative sensitivities, you can identify the risks they expose your business to. You may be most familiar from the news with the risk of unauthorised people accessing (data theft) or modifying information (e.g. ransomware). These are Confidentiality and Integrity risks. Some assets may also create an impact if they cannot be accessed. For example, there was a massive denial of service attack against Estonian government services, banks and media outlets in 2007. Estonia had been significantly more advanced than most other countries in moving their services online, including national elections. The attackers, widely believed to be acting on behalf of Russia, could present a credible threat to the Estonian state just by demonstrating that they could deny access to these critical services.

Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability have been considered the iron triangle of information security for a considerable time. At a more nuanced level, and under certain circumstances, you may want to be sure that you know precisely who or what system created or modified a particular asset or piece of information, and you may want to have proof to prevent that person from denying that they made the change. These represent the principles of Authenticity and Non-reputation.

These security principles are useful when considering what risks your assets are exposed to and how your organisation would be impacted if they were breached. For example, you are unlikely to be concerned about the Confidentiality of the information on your website; it exists to be viewed by as many people as possible. But you will be more concerned about its Availability because if people can’t access it for a significant period, this might undermine confidence in your business and reduce the marketing value you are getting from the asset. And you will be very concerned about the Integrity of the information on your website. If someone changed the content, not only would it undermine the marketing value, but anything offensive could cause reputational damage and expose you to legal action.

Defining Risk Severity

Starting with the broad asset Classifications you selected earlier, you can begin to identify what risks they present and what impact these risks might have on your organisation. In an ideal world, you would want to put a price on that impact, but as a starting point, you can identify the qualitative impact according to a series of defined categories. We use the following broad definitions:

| Risk | Description |

| None | The risk does not exist, or it would have zero impact. |

| Very Low | This risk would present a minor irritation but would not require any remedial action or reallocation of resources. |

| Low | The risk would cause some disruption to the business and could disrupt certain operations for a limited period until you have addressed the issue. If this recurred, there could be broader reputation damage. |

| Medium | The risk would have a significant impact and would require the reallocation of resources for some time from other tasks to remediate and recover from the event. There may be some loss of revenue and reputational damage that would require protracted efforts to recover from. |

| High | The impact would be severe, with the potential for widespread loss of revenues, significant legal action and fines, loss of access to one or more significant markets, and/or reputational damage that would take more than a year to recover from. |

| Very High | The impact on the organisation would be life-threatening, with the potential to make it insolvent as a result of lost revenues or reduced market access. |

At this stage, you are ignoring whether you have security that would make the risk unlikely or reduce the impact if it occurred. You are trying to define the inherent risks that exist irrespective of your security.

Risk Identification

The matrix below illustrates what the result might be from this risk identification exercise, with some examples of their impacts:

| Open | Sensitive | Confidential | In Strict Confidence | Specific | |

| The risk that an unauthorised individual accesses this resource | None | Low | Medium | High | |

| The risk that an unauthorised individual modifies this resource | Medium | Low | Medium | High | |

| The risk that this resource is destroyed or made unavailable | Low | Low | Low | High | |

| The risk that bulk quantities of sensitive personal information about employees is leaked | High (Personnel Sensitive) | ||||

| The risk that significant quantities of Client Confidential information related to a Government Client is leaked | High (Client Confidential – Govt) |

All of this may seem like a lot of work, but there are a few principles to keep in mind to make it less daunting:

- At this stage, don’t even start to think about how you will protect the assets; you are just trying to characterise the assets you have or expect to have.

- Don’t allow perfect to be the enemy of good; you need to get started and apply the Pareto principle in spades. Over time, you can evolve and improve it.

- Avoid being drawn to defining too few or too many classifications or allowing the majority of your assets to gravitate to a single classification. The purpose of this exercise is to be able to differentiate between things consistently. Too many options undermines consistency, and too few prevents differentiation.

1 thought on “CS4NSP Episode 2: Show me the Value – Assets and Risks”

Pingback: CS4NSP Episode 4: Devices Deserve Zero Trust from the Outset - Digility Ltd