Brief at the Start

Go straight to the full length version

It is uncomfortable to say that we don’t trust people we know and work with, but trust is rarely unconditional and never binary

The concept of trust is central to security. People trust is very important because nearly all digital systems exist to serve or interact with people, whether directly or indirectly. We all understand that there are some people we trust – Good People – and some we don’t – Bad People. We want Good People to access Assets and prevent Bad People from exploiting them.

But the world is far more nuanced than that, and we need to be embrace this. In our non-digital life we trust different people to different degrees depending on what we know about them and how they interact with us. You can use a the characteristics you know about a person to build a chain of trust that spans both the real and digital worlds:

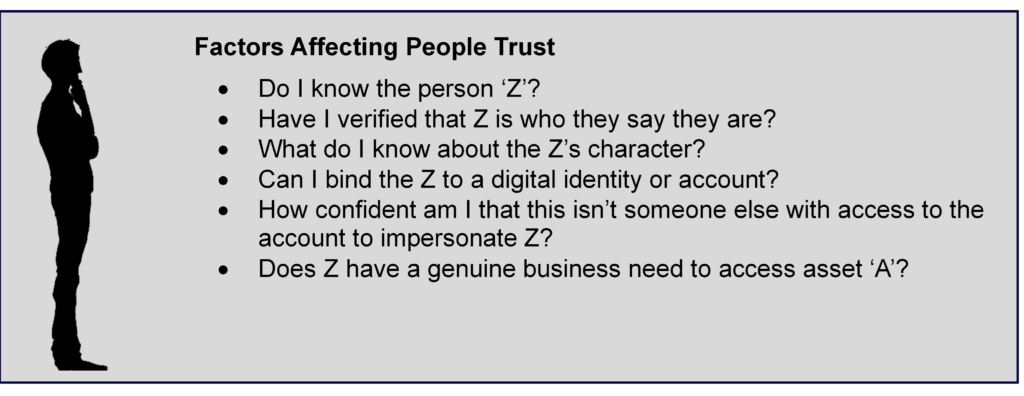

- Do I know them as a person?

- Has their actual identity been verified?

- What do I know about their character and behaviour?

- Can I be sure that their digital persona is bound to their physical one?

- Am I confident that someone else couldn’t access or or otherwise impersonate their digital persona?

- Do they need to access the asset in question?

But you need to recognise that chains are only as strong has their weakest links.

The level of trust that you need will be proportionate to the Asset value and level of Risk that we discussed in the previous Episode about Assets and Risks. By establishing a range of different TRUST PERSONAS you can identify which level of trust applies to the various Asset Classifications and Risk Severities.

Get the Full Version

What is Trust?

Trust is at the heart of all security and risk management. Do you trust your bank to be a safe place to put your money? Do you trust a school to look after your children? Do you trust your doctor to correctly diagnose and treat a condition with your interests in mind? Do you trust the taxi driver you hailed late on a Friday evening?

Cyber security is no different, and people are at the centre of that concept of trust. You are dealing with honest people you trust with assets and resources so they can do their job. And also dishonest and dishonourable people who wish to cause you harm. Sometimes, bad people will try to cause that harm directly, but more frequently they will look to exploit people that we trust to achieve their aims. We described in our Introduction in Episode 1 how our model for security is based on enabling trusted People to access the Assets they are authorised for.

But trust is an analogue measure; its a continuum. You might know a few people in the world who you would trust with your life. But equally, you may also know of a few others you would not trust and would be actively suspicious of whenever they passed close to your life. Between those extremes, is everyone you know and who you trust to a lesser or greater degree. Some you would trust with your children. Others you might trust to wash your car. The person who washes your car isn’t inherently less trustworthy than the childminder. It is just that you are taking greater risk with the person who will be looking after your children and so need to be able to trust them more. You have probably conducted greater due diligence on them because the consequences of making a wrong decision are much more significant.

Within our businesses, we tend to say that we trust our employees and partners. It is uncomfortable to say otherwise. After all, once we have chosen to recruit an individual, it seems odd to say that we don’t trust them. But in day-to-day life in a business, the same spectrum described above exists and is used. Not everyone in the organisation is given access to the bank accounts. Certain conversations take place in private. Like the examples of the childminder and the car washer in the previous paragraph, we have some roles where the potential impact of choosing the wrong person is significantly greater than others.

So, trust isn’t absolute in our work lives just like it isn’t in our personal ones. And deciding if you trust someone with a digital asset should be similar to physical assets. The only difference is that it is not as intuitive in the digital world, as it is when dealing with bank cards, door keys, and cash.

There is a further complication in the digital world though. It is a weird quirk of human nature that people are more inclined to trust what a computer tells them than when a human tells them something. When I was in the Army, it was fascinating to see colleagues assume unit locations on a computer screen were totally accurate. When looking at a marking on a paper map, these people instinctively knew that the location was only as precise as the six-figure grid reference reported and someone’s marker pen. They also knew that it would only be updated periodically. They knew that the computer was being fed the same information source. But they would still be seen zooming into the map and questioning the location down to one metre’s accuracy.

To combat these challenges we have broken down the concept of people trust into a number of contributing factors as illustrated in the diagram below:

Figure 1 – The Factors Affecting People Trust

Do I know this person?

The first question you need to answer is whether you know the individual. Have you met them before? Do you know them as a genuine, unique, physical person?

Even if you know them, have you verified that they genuinely are who they say they are? Have you verified their identity, such as by viewing their passport?

Is this person trustworthy?

In some circumstances, you may need to gain further evidence that talks to the person’s character. You might review character references from previous employers or associates. Or conduct a criminal records check. As the sensitivity of assets increases, the case for increased levels of vetting will rise. Sometimes a client might insist on greater vetting, as is the case with Security Clearances required by certain Government Departments when an individual will handle classified material. BS7858 is a standard dedicated to security screening individuals employed in a security environment.

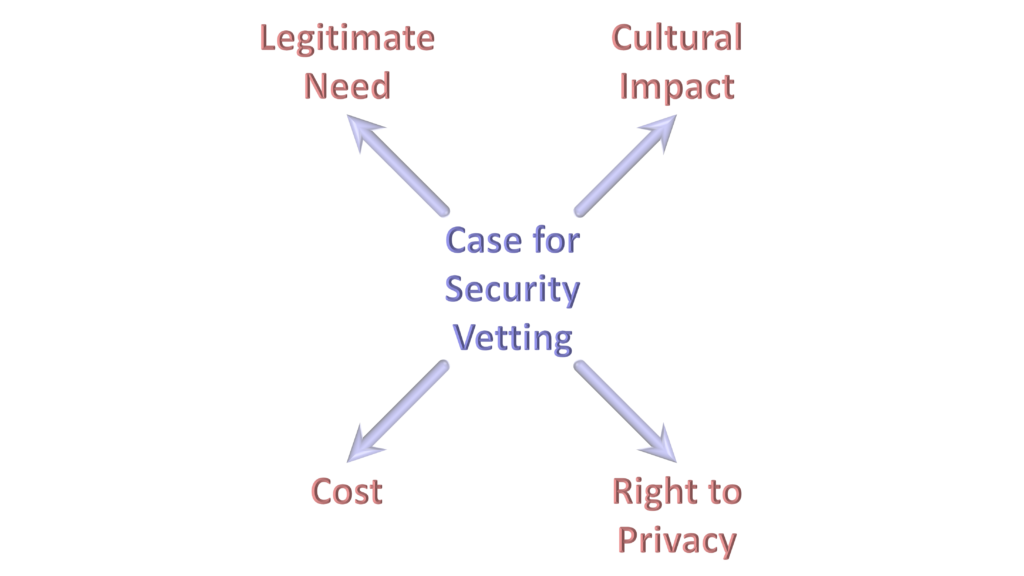

There will be a balance when deciding how much vetting you apply to individuals. First and foremost, you must identify whether you have a legitimate business need to conduct the vetting. For example, any company can do a basic DBS check for criminal records, but the next level of DBS check is primarily for certain professions, such as the judiciary. The most enhanced checks are restricted further for specific regulated activities, such as working with children and the more vulnerable elements of society. Many of these types of vetting have legislation restricting their use to balance the individual’s right to privacy against the risk being mitigated. Even if you have the right to conduct vetting, you may need to consider whether the benefits warrant any impact on the organisation’s culture and the cost of the exercise.

Figure 2 – Balancing the Case for Vetting

If vetting isn’t appropriate, you might use Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs) or similar legal terms as a proxy to establish some degree of trust. While this won’t establish explicit trust, you can enforce the terms. It creates a deterrent effect and may enable the recovery of damages in case of a breach.

This character trait can also be influenced by initiatives such as training and awareness. An individual may not be inherently untrustworthy, but their lack of knowledge and familiarity with policies may make it more likely that they will act dangerously or irresponsibly.

Is Digital Z bound to Physical Z?

The adage “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” is as true now as it was when the New Yorker published the cartoon in 19931. We’ve all seen social media accounts that appear to be our friends, only to find that they are imposters. To make them believable, they may have been identified with the individual’s name, genuine photographs from their life, and certain other facts and characteristics. They may have convinced mutual friends to ‘like’ or ‘friend’ them and built a stronger ‘web of trust’. But they are not who they say they are. This is possible because there are no requirements on those social media platforms to validate the identity of the person creating the account.

When a new employee or associate starts in your organisation, you can validate their identity before giving them access to sensitive assets. Doing this binds their physical identity to their digital identity. Generally, the process requires some level of face-to-face checks and transfer of login details.

Being confident in this link between the physical and digital person is important. Without it, all the physical checks described earlier in this article will be irrelevant.

Can Z be Impersonated?

So, you have validated the physical identity and have bound that physical person to a digital account. But what if someone else could access the account and act as though they were Z. It’s critical to choose the most appropriate level of security around user accounts, proportionate to the assets at risk.

For the lower-risk roles and assets, you may be content that accounts are only protected with strong passwords. But passwords are one of the most vulnerable forms of security. They are prone to human weaknesses. Despite decades of press coverage that explains the hazards, people still choose weak passwords like ‘Password1234!’. Or they use the same password in multiple different places. The first habit is easy to guess, and the second means that if one of those places is hacked and the password compromised, then every other account or application that uses it can also be accessed.

Even if an individual uses a strong password that hasn’t been used anywhere else it becomes easier to break a password every year as a result of advances in technology2. Hive Systems estimated that in 2018 an 8-character password using uppercase, lowercase, numbers and symbols would have taken 8 hours to break, but this reduced to 5 minutes by 2023. And those estimates will be essentially eliminated once quantum computing is available at scale.

So, any asset of more than a trivial value should be given greater protection. The most effective and efficient measure is to request a second factor, such as a one time code generated by an Authenticator app on the individual’s phone, when they log on. This means that even if the password is compromised, a hacker is unlikely to be able to log on without access to the user’s phone as well.

You may need to restricted access entirely for the most valuable assets that present Very High severity risks so that they can only be accessed from secure, trusted locations. This reinforces the digital security controls with the physical security ones.

The Situation with External People

The requirement for people outside your organisation is similar but the challenge is frequently more demanding. You may need to decide how much you trust their organisation. Has the organisation demonstrated that they conduct similar checks on their people as you do on yours? Regardless, it is likely that you will have a lower level of trust in a third-party person than you will in your own organisation.

Only as Strong as the Weakest Link

It should be clear from many of the factors described above that trust relies on each link in the chain. If there is one weak link, the entire chain may be flawed. For example, you may go to the highest levels of due diligence into the individual. But if care isn’t taken to ensure the account access is given to the person you reviewed, or if the account could be compromised relatively easily by a third party, then the due diligence has been a wasted investment. Vice versa, if you have all of the controls in place to protect the account and to issue it to the right person, but you haven’t done appropriate checks on the individual, then the only thing you can be confident in is that an individual you have no reason to trust is able to access resources you value.

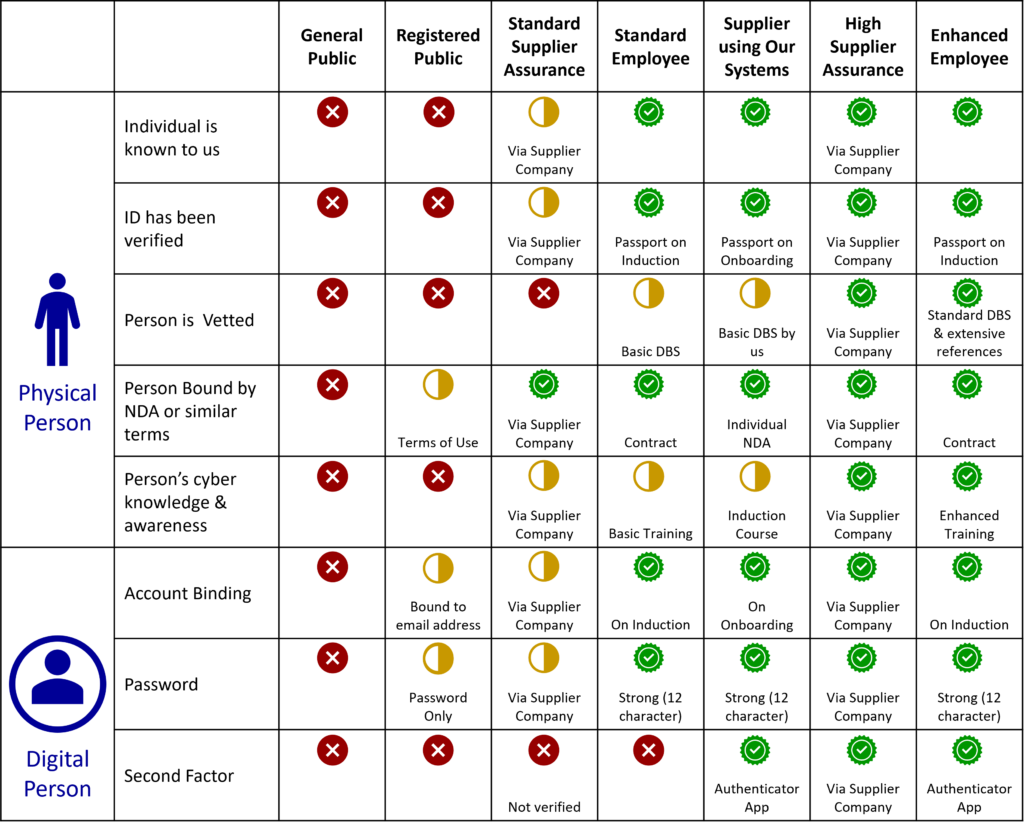

Trust Personas – Defining the Different Levels of People Trust

Now that you have considered which factors are relevant to your organisation you can define a number of different Trust Personas. The matrix below gives an illustrative example. At the left end, we have the general public, whom we have no reason to trust. As we progress to the right, we see different personas that will have earned higher degrees of trust. When we come to apply the model we will be able to require different Trust Personas for different types of access to different assets.

Note that the figure above is illustrative and should not be taken as a recommended set of Trust Personas. For example, in the figure, the Standard Employee does not have Second Factor Authentication (2FA or MFA) enforced. Given how straightforward 2FA is to apply and use these days, we recommend enabling and enforcing it by default. It not only improves authentication security significantly, but by consistently applying it to all staff we can reduce confusion that might arise when some needed it and others did not.

Once trusted, how much authority will you give

Being able to trust that the person gaining access to an asset is genuine and authentic is a critical step. This is the process of authentication, and as we have described, there will be varying degrees of trust from zero to the most stringent levels of vetting and account security. But authentication is just about identity. We also need to ensure that the person has authority to access the asset in question. Authorisation is all about permissions; giving the access rights after confirming the need and reviewing this on a regular basis.

The topic of authorisation is a lengthy one in its own right, and will be discussed in greater detail when we bring the model together in Episode 8. It introduces the requirement for processes and policies that counter a variety of different risks and hazards. Some key examples are detailed below, but a detailed description is outside the scope of this article:

- Joiner/Mover/Leaver Processes. These are the processes to be followed when an individual joins the organisation, moves from one role to another, and leaves the organisation. It should validate all of the permissions that the user requires to fulfil their role and eliminate any that are not needed.

- Re-Certification. A periodic review of a role or permission where everyone who still requires it is confirmed, and everyone else has that permission removed.

- Segregation of Duties. Defining conflicting roles that the same person should not hold. For example, the person authorised to sign a purchase order should probably not be allowed to authorised an invoice.

There is also the more important question of managing the managers. How are permissions that give the individual the power to manage access itself, and the various other security controls. We cover this in Episode 8 – Castle Keys and other Exceptions.

Summary

We have introduced the factors that contribute to our trust in a persons digital interaction. It is clear that different levels of trust are required in different contexts. To help with this we have shown how to define a set of Trust Personas. These Trust Personas are the building blocks of a set of People controls to enable those who need access and deny those who do not. When we apply the model at the end of this series of articles you will see how these Trust Personas are used to enforce this business enablement according to the different types of Assets and Risks described in Episode 2.

2 thoughts on “CS4NSP Episode 3: Do you trust me? Why?”

Pingback: CS4NSP Episode 4: Devices Deserve Zero Trust from the Outset - Digility Ltd

Pingback: Avoid Issues in Operations – Be More Secure by Design - Digility Ltd